Until my interest in astronomy was resurrected in 2015 I never really gave city lights a second thought except when they shined through my bedroom window at night or when I considered the plight of sea turtles. As a Florida resident the problem with municipal and private property lighting along beaches was well known through the efforts of activists and subsequent legislation that seems to be making a positive difference for turtle hatchlings along at least some beaches. As a student of horticulture, I was also aware of the effect light has on plants. Not just sunlight, but also studies documenting adverse effects to trees by high power highway lighting. It seems artificial light eventually stunts growth rather than encourages it - more light isn’t necessarily better for plants.

Back to stargazing in the suburbs… it wasn’t until my neighbor undertook a home improvement project replacing all of the incandescent floodlights around his home with even more and brighter LED floodlights that this problem of light pollution became real for me. He happily reported it used only a fraction of the power of his previous bulbs but now his property is lit up like the periphery of a prison - all night long, every night. I started reading about light pollution and learned about “light trespass”, the Bortle scale, and other related terms. As an urban planner I was interested to see a story entitled “Seeing Stars” on NBC’s Sunday Today show about a town in Wet Mountain Valley Colorado which has enacted (and enforces) strict nightime artificial lighting control measures to protect and promote their astronomy-based tourism economy. Read more at www.darkskiescolorado.org and watch the NBC Today show video. I also found and read Paul Bogard’s The End of Night: Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light which for me was eye opening.

My Back Yard

My suburban lot experiences light trespass from three sides over the 6-foot high wood fence.

Strong light pollution from urban Baton Rouge makes views to my west pointless - except for bright objects such as planets or the moon. I’ve found if I set up in the right position in my back yard I can use the roofline of my house to block most of the troublesome neighbor’s security lights, but neighbors in other directions have motion detection floodlights which keep turning on and off as cats or racoons pass by. Of course this also means the roofline blocks large portions of the sky. It’s resulted in drastically decreased use of my telescopes and it makes me want to move to the country.

Local Observatory

LSU has an observatory and learning center at Highland Road Park, about 9 miles from my home in Baton Rouge. The observatory is opened to the public most Friday nights, and a line forms for a glympse through the eyepiece of the big scope. It seems they discourage the public from bringing their own equipment out there. I’ve done it on a night the facility wasn’t open, and it is darker there than at my home. The sky to the south is dark as it overlooks a swamp - Alligator Bayou and Spanish Lake - but skies to the west are still brightened by the lights of metro Baton Rouge. There’s an internal gate at the park which restricts visitors to the front parking lot along Highland Road on nights the observatory is not open, so you have passing headlights to deal with. And, most of BREC’s parks officially close at nightfall so I’m probably not supposed to be there after dusk anyway.

BR Astro Club

The club meets regularly at the above observatory, and it controls a piece of land well west of Baton Rouge off of I-10 overlooking the Atchafalaya Basin which they make available to members. I should join and try it out, but it gets back to my lack of time to participate as the round trip driving and loading / unloading of equipment adds two-to-three hours to each trip.

Finding Other Sites

I’ve found that my fondness of car camping (with a tent) combines well with astronomy. Public lands including state parks and especially national forests offer some campsites in remote, relatively dark sky sites. The trouble is often finding a sufficiently large clearing away from other campers to set up your gear. At popular campgrounds some visitors brightly light up their campsites with strands of LEDs and bright lanterns, negating any advantage of dark skies. But if you find the right site with the right neighbors and good weather the views can be terrific. I don’t sleep well on an air mattress anyway so why not stay up and stargaze.

Light pollution maps are helpful in finding potential dark sky observing sites. I’ve used darksitefinder.com to identify areas in which I’ll search for campgrounds using reserveamerica.com or the US Forest Service website.

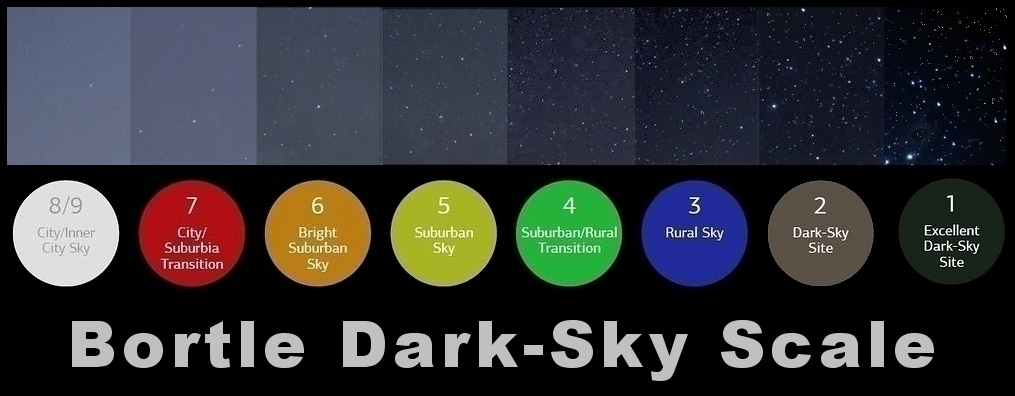

Bortle Scale

It was while reading The End of Night mentioned previously that I was educated about the Bortle Scale of light pollution and from there discovered light pollution overlays on web maps. It is facinating and a bit distubing to look across our country and see so little uninhabited areas east of the Great Plains. I look with interest at pockets of dark blue or grey which are not already publicly owned forests or preserves. Is that land available for a retirement home?

This graphic was found posted in the Cloudy Nights forum by BYoesle. link

This graphic was found posted in the Cloudy Nights forum by BYoesle. link

According to this scale my suburban home is in zone 6 or 7: Bright Suburban to Suburban-Urban Transition. It is red on the light pollution map. I suppose gauge it looking at the zenith, but it is fair to claim a range of Bortle values depending upon which compas direction one is facing. To my east skies are much darker than to the west. Before my neighbor’s LED floodlights I enjoyed searching for brighter comets and star clusters from my driveway and particularly targets at the southern horizon. Now I don’t bother.