As Baton Rouge is just an hour’s drive from the Big Easy, we get down for visits with friends and sightseeing several times each year.

History

Below I offer my big, bad overview of the history of New Orleans; based on a variety of sources from the web or print books I’ve read over the years. I’ve failed to properly document them, so if this were a middle school English paper I’d get an “F”. I’ll strive to track down these sources, though I know some came from the Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans - prcno.org. And another great reference is “Gateway to New Orleans: Bayou St John. 1708 - 2018.” by Hillary Irvin. A third terrific book is “New Orleans Then and Now” by Richard Campanella.

In early 2005 the population of New Orleans was over 450K, a bit higher than Atlanta at 430K. Katrina flooded 80% of the city. Over half of the population left, leaving the total resident population less than that of Baton Rouge at 228K. Today, New Orleans’ population remains less than it was in 2005, but it is now approaching 400K. (Atlanta is flirting with 500K.)

Why does New Orleans matter?

Though not the first, New Orleans grew to be the nation’s largest Gulf of Mexico ports. It serves the entire heartland of the nation via the Mississippi. Port NOLA, oil & gas, and tourism are the city’s top industries. Initially, the port’s commodities were sugar, rice, cotton and other grains. All of these have now been displaced to other, more rural locations along the river, which continues to be instrumental in their transportation.

A Caribbean City

New Orleans is the nation’s only “Caribbean” city. Why? What about Tampa, Miami? Miami is far too young. Tampa was never as large, nor retains as much Spanish influence as New Orleans. Key West has similarities, but being landlocked was too small and too far away from agricultural fields. New Orleans is and has always been a vitally important point of trade and, as such, is a cosmopolitan city with immigrant populations from many nations.

Why here?

Hint: It’s not just the Mississippi River.

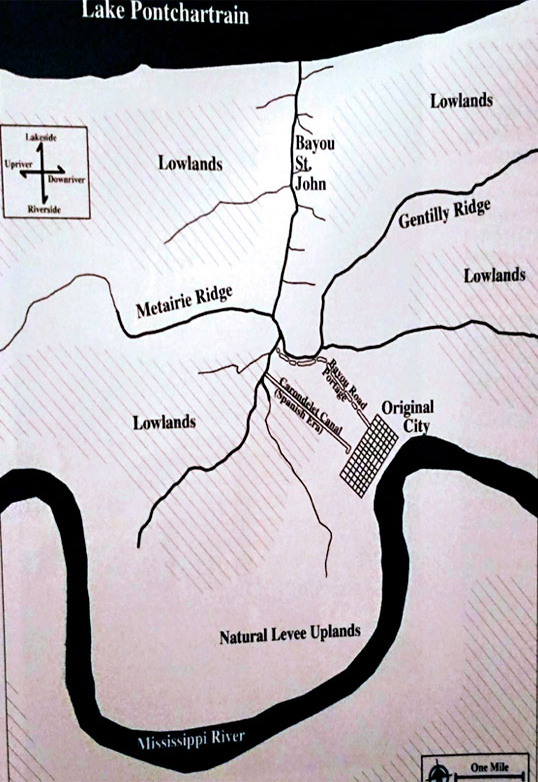

Earlier French and Spanish settlements along the Gulf coast lacked high quality agricultural lands. This is why settlement continued west from Mobile and Biloxi. The location of New Orleans - the Vieux Carre or “Old Square” offered the trifecta: a Mississippi River port for downstream goods, locally available rich agricultural lands, and a “back door” via Bayou St. John and Lake Pontchartrain out to the Gulf of Mexico.

Why not at the mouth of the Mississippi? (Present day Venice, Louisiana) The Bayou St. John location saved 110 miles of treacherous river travel, and more local agricultural land was available further upstream.

Why is it called the Island of New Orleans?

High ground existed only along the rivers and bayous due to accumulations of sand and sediment deposits from annual flooding. Upstream from New Orleans the western edge of Lake Pontchartrain nearly reaches the Mississippi River. Today this is the Bonnet Carre Spillway. It is marsh, so New Orleans effectively is an island between the river, the lake and the spillway. But historically the Isle of Orleans was much larger. It extended all the way north almost to Baton Rouge. The Bayou Manchac waterway linkinging the Mississippi River to the Amite, through Lake Maurepas and Lake Pontchartrain and out to the Gulf through the Rigolettes formed the boundary separating Spanish Orleans from English and then United States lands. Little old Bayou Manchac, which I’ve written about on my paddling post, was an international border!

1721 - 1723 - The Vieux Carre was laid out by the French along an arc of high ground along the river. Generally, the further away from the river you go, the lower the topography. This is why New Orleans is a “bowl”. It is encircled by levees intended to protect the city, and it captured and held Katrina’s flood waters. Where did the levees fail during Katrina? Nearly all were along the north side: the Pontchartrain lakefront and the Industrial Canal.

Beginning with 5 blocks in 1721, the Vieux Carre expanded to it’s full 66 blocks. Today there seem to be more if you count them, but this is primarily due to alleys. Initially a French settlement, this changed following the French and Indian War as France was losing. The King of France transferred ownership of New Orleans to his bourbon brother, the King of Spain. It took two years for the residents of New Orleans to learn of this transfer (1769). The city remained under Spanish rule for 60 years, but retained French as the primary language as it was settled by a mix of nationalities.

Americans

Louisiana Purchase occurred in 1803. New Orleans was the gatekeeper city for well over 800 thousand square miles of North America. The influx of “Americans” from New England and the Atlantic coastal colonies such as the Carolinas and Georgia begins in earnest in 1803.

Lagniappe

A little something extra… Below is just a little bit more about terms and concepts central to New Orleans, some extending throughout Louisiana.

Bourbon

Contrary to a lot of opinion, Bourbon Street is NOT named after the Kentucky whiskey. When the city was founded, it was named after the French Royal Family, the “House of Bourbon”, which produced a number of French kings, including Louis XIV, The Sun King.

“Vieux Carre” is French, why does it look Spanish in character?

Fire. In 1788 a fire destroyed over 850 French-style wooden buildings. It was rebuilt following more Spanish architecture and building techniques - and more masonry rather than wood in an effort to avoid future fires.

Crescent City - Pie Slices

Since the waterways were the mode of transportation, land was only valuable if it had access to waterways. The French continued their practice of subdividing land into “arpents” or wedge-shaped slices radiating away from a river or bayou. The higher land was closest to the river, so this is where buildings were constructed, behind that were the crop fields, still further back the land often got very low and wet. This was the “back swamp”. The crescent shape of New Orleans is a direct result of subdivision of these early arpent-shaped plantations both up and down river from the Old Square. Actually, this practice continues up to Natchez.

Faubourgs

French for “false towns”, faubourgs arose surrounding the initial city which was contained within the ramparts of the Vieux Carre. Faubourgs pushed upriver, downriver and away from the river toward Bayou St. John. The first was Faubourg St. Marie, just upriver, in the area now occupied by the central business district. This was the initial “American” section of the city and the CBD has largely obliterated St. Marie. Another - the Faubourg Treme - grew immediately behind the downriver half of the Vieux Carre toward Bayou St. John. It was largely settled by free persons of color. (The last e in Treme should be accented with the e acute é , though getting it to display from markdown is challenging.)

A third - Faubourg Marigny - was developed by it’s French Creole owner on the downriver side of the Vieux Carre. As the city continued to grow with influxes of immigrant populations and “Americans” moving west, each tended to settled according to their nationality and social class.

Canal Street

The canal that never was. It’s a misnomer. Canal Street follows a route of a proposed canal linking Bayou St. John to the Mississippi River. Too many locks would be required so it was never constructed. Today, the wide right-of-way of Canal (and other New Orleans boulevards) are often called “the neutral ground” as they separate neighborhoods of peoples having different demographics and social class. The Vieux Carre was considered “low class Spanish Creoles” by the Americans on the St. Marie (CBD) side of Canal Street.

A Melting Pot?

Not really, certainly not at first though it is more-so now. New Orleans was a mix when looking broadly across the city, but quite segregated when examined neighborhood by neighborhood, with a couple of exceptions such as Treme. The term “neutral” in neutral ground referred to the gap dividing boulevards. It was a literal buffer zone between races or classes of people. The early French were aristocracy and businessmen, not outcasts like the Acadian “cajuns” who settled elsewhere in Louisiana. The Spanish were traders and artisans. Both groups were largely catholic. Free blacks arrived from what is now Haiti, as did ship loads of slaves from Haiti, other Caribbean ports, from American Atlantic seaboard ports such as Charleston and Savannah, and directly from Africa. Also, there remained native Americans (“indians”) who refused to be displaced from their ancestral lands. Here is the origin of the “Mardi Gras Indian”. Protestant Anglo Saxons migrated from the 13 colonies, and traders from other nations: Italians, Germans, etc. arrived with the vessels arriving at New Orleans.

Mardi Gras

New Orleans’ first Krewe and Mardi Gras was organized by upper class creoles / Spanish residents. They mimicked the celebrations begun only a few years earlier in Mobile. The celebration quickly caught on in New Orleans, with new krewes being formed by white Catholics, and others by minorities including the free blacks of Treme.

Military Parade Ground

Jackson Square has always had a military theme. Prior to the erection of the statue of Battle of New Orleans hero Andrew Jackson (and the Americanization of the place name), the square had the Spanish name Place d’ Armes. It was a military parade ground adjacent to the river. St. Louis Cathedral (catholic) was built prominently at the head of the Place d’ Armes, and it was flanked by governmental buildings the Cabildo and the Presbytere. Later, a developer built the Pontabla Apartments on both sides of Jackson Square, framing it.

The Lower Quarter

Called “lower” because it is downriver, this is the area of today’s French Market, the US Mint anchoring the corner, and the Ursuline convent two streets in. Built in 1750, the convent is one of few surviving French colonial structures in the Mississippi valley. While the French Market dates only to a Works Progress Administration era project, a few components are older. And for sure this area of the Vieux Carre has been utilized as a trading and goods transshipment point since its founding. New Orleans’ US Mint is now a museum, but it was the first major mint established outside the northeastern states - pointing to the significance of this city as a place of business and exchange, and it is the only one where confederate coins were struck.

Streetcars

St. Charles Avenue forged west from the old square to Carrol Town, now part of New Orleans and shortened to “Carrolton,” essentially bisecting each of those pie-shaped plantations and facilitating their development. this intensified with the installation of the streetcar, as “streetcar suburbs” grew densely into some of the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods. It mirrored the arc of the river, emphasizing the “crescent city” layout we know today. “Spokes” in the crescent are the former boundaries between adjacent plantations. We see them today as Louisiana, Napoleon, and Jefferson Avenues, among others. Note the contrast in the sizes of lots and placement of buildings between the French / Spanish Vieux Carre and the American “Garden District” neighborhoods. The former feature zero setback buildings on narrow streets, usually with any landscape reserved for interior courtyards. The latter place the homes in the center of each lot, surrounded often by lush gardens - like a wedding cake on display. Urban development vs. suburban.

The Tremé

This “first black neighborhood in America” is the birthplace of jazz, had the first black-owned newspaper “The Tribune”, and featured a unique community where families of many races lived side-by-side. Some of the time it was harmoniously - such as when fully integrated schools were the norm long before Brown vs. Board of Education. Tremé is the community from whence the US Supreme Court Case Plessy vs Ferguson originated, resulting in “Jim Crowe” practices becoming the law of the land. The 2008 documentary film “Faubourg Tremé: The Untold Story of Black New Orleans” is very insightful.

Monumental Controversy

New Orleans, like many other cities and towns (not just southern) are removing, or being pressured to remove, monuments to the confederate military, to docile-appearing indians, and others. To date, New Orleans has spent well over $2M to remove four key monuments:

- Robert E. Lee - in Lee Circle

- P.G.T. Beauregard - at an entrance to City Park

- Battle of Liberty Place / Crescent City White League

- Jefferson Davis - on Canal at Jeff Davis Pkwy.

This was accomplished under the leadership of former Mayor Mitch Landrieu, son of former New Orleans Mayor “Moon” Landrieu, (and his sister is the former U.S. Senator Mary Landrieu.) Read “In the Shadow of Statues” by Mitch Landrieu for a thoughtful discussion of this process. If you read it, or even if you don’t, you should consider the answers to the following questions before you jump to conclusion.

- What was the purpose of these and all Confederate monuments? Celebrating victory?

- When were they installed? Immediately following the war during reconstruction, or later during the Jim Crow south?

- Who paid to install them? Money often reveals motive.

Lately, in 2020, this topic has risen to national attention and many states, cities, counties and communities are struggling with how to address this issue of the confederacy.